A parked truck is just the latest witness to our region’s endless development

By Bill Newcott

Illustration by Rob Waters

From the April 2024 issue

The source of the melancholy that sweeps over me as I make the turn off Cedar Grove Road onto Mulberry Knoll, near Lewes, is at once obvious and elusive.

At the southwest corner spreads a cornfield — at least, as of this writing. It is midsummer: a time of growth, green and hopeful, the stalks topping out just at eye level. Far, far in the distance, a stand of trees marks the field’s western boundary; a here-and-no-further wall that has, perhaps for a century or so, defined the demarcation between agriculture and nature’s last stand.

And there, parked diagonally near the intersection, is an old Chevy panel truck, lovingly maintained yet defiantly utilitarian. “247 Single Family Lots For Sale,” a sign on the truck proclaims.

I sigh as I make the turn on Mulberry, my eyes lingering on those gently swaying stalks, wondering if this is the last season that these acres will be doing what land is meant to do.

Then again, since I am the sort of person who always second-guesses my perspective, I almost immediately confront my sadness head-on. Is the prospect of streets and ponds and fountains and driveways and row after row of Pete Seeger-inspired tiny boxes really the end of the road for the land? A cul-de-sac of perpetual infertility?

I back up and take a photo of that truck in the cornfield. Later, I don’t even need to look at it to understand its utter insignificance: My single frame contains not the lifespan of that land, but precisely 1/25th of a second in a continuum that predates me; that predates human occupation — and that will long outlive us.

Today, the corner of Mulberry and Cedar Grove sits about 4½ miles due west of the ocean. Every schoolchild knows (or should know) that was once not the case; that in ages past, during a planetary high-water mark, this patch of land didn’t even exist. Then came a succession of cold freezes; glaciers marching south from the North Pole sucked up enough global water to leave coastal Delaware’s shoreline far east of its present location.

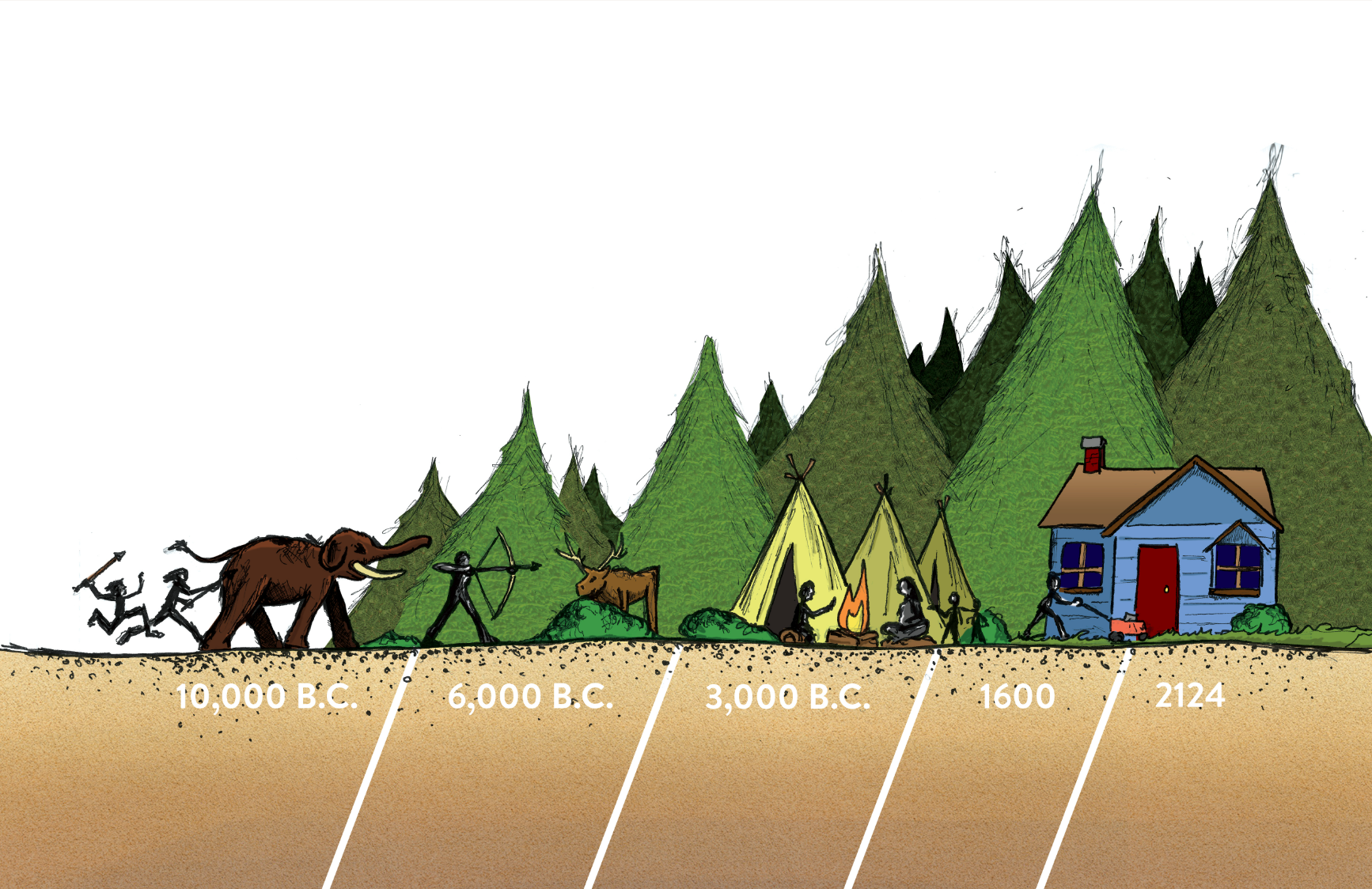

The land beneath our feet is not unaccustomed to radical change. Not by a long shot. If the truck in the cornfield were a time machine, and we were to sit in the cab, we’d have endless opportunities to post prescient advertisements on its side.

The Truck in the Cornfield sign, circa 10,000 B.C.:

“New Property Now Available!”

The first human feet to trod across what is now the corner of Mulberry and Cedar Grove may have done so as recently as 10,000 years ago. These were the descendants of the intrepid (maybe a little foolhardy) people who crossed the land bridge that existed between Asia and Alaska. Pushing southeastward over centuries, those first North Americans finally reached a dead end at the sea we call the Atlantic. In what would, an eon later, become lower Delaware, they found what amounted to a glorified sand spit: spruce trees, pines and grasslands clinging to life atop a dry, undulating landscape created by granules swept downstream in melt runoff from the retreating glaciers that had approached as close as today’s Pennsylvania.

In the patchy foliage that covered the land, the first human visitors killed mammals large and small using stone spearheads. Mastodons were afoot (a tusk and molar have been dredged up off the Delaware coast) and maybe even camels — eventually killed off with an efficiency that had already resulted in their early extinction elsewhere as the wave of hunt-happy humanity worked its way across the continent. For sure, those earliest coastal Delawareans hunted white-tailed deer — although, in the estimation of many 21st-century residents surveying their devastated flower beds, they didn’t bag nearly enough of them.

Those hunting grounds were far more expansive than what we see today. The sea level 10,000 years ago was more than 100 feet lower than it currently is, putting the shoreline about 30 miles farther east than it is today. A day trip to Cape May would have involved a long walk interrupted by a strong swim across a rushing, but narrow, Delaware River.

No matter how you feel about the cause of rising sea levels, it is an undeniable fact that we are sitting in the path of a slow-motion tsunami. Somewhere off Dewey Beach, 100 feet or so under the churning hulls of advancing oil tankers, lie the remnants of someone’s long-ago hunting expedition: some spearheads, perhaps a few shards of pottery. About 9,000 years ago, the sea’s rise was at a full gallop: more than 3 feet every century. That rate has slowed considerably, yet the sea is still coming, still promising to swallow every trace of humanity in its path.

The Truck in the Cornfield sign, circa 6,000 B.C.:

“Hunting Season Now Open!”

Imperceptibly, temperatures rose, and the glaciers continued their retreat. With the shoreline now about 10 miles east of its present location and continued enrichment of the soil via wind-blown dirt, decaying plants and animal poop, humans began to settle in.

“On the coastal plain, with the water table extremely high, we would have had primarily pine trees, like today,” says Bob Tijade, a retired University of Maryland forester and co-author of “Beneath the Canopy: A Historical View of Forestry in Delaware.”

“Then, moving inland, the low-lying areas would have had Atlantic white cedar and bald cypress. Finally, there would have been a mixed hardwood forest dominated by oak and hickory trees.”

That’s a lot of trees supporting a lot of wildlife, and the human population flourished.

Mounted in a glass case at the Nanticoke Indian Museum near Millsboro is a collection of stone spearheads found around here. Fashioned from jasper and silica-studded chert — probably dug up in the northern reaches of the Delmarva Peninsula — their workmanship is remarkable: A pointed tip with a notched lower portion that facilitated fastening to a shaft with leather straps. They are, at the latest, about 6,500 years old.

Favorite hunting spots included hundreds of shallow depressions that filled with rainwater each spring, drawing wildlife from the thickening forest. In the 20th century, those depressions — probably created by howling winds back when coastal Delaware was one long sand trap — remain prime locales for finding ancient spearheads. They’re commonly called whale wallows; a name coined by early European settlers who reasoned they’d been created by stranded whales following the ebbing of Noah’s flood.

The Truck in the Cornfield sign, circa 3,000 B.C.:

“New Stick-Built Homes Near the Beach!”

Around the time prehistoric engineers were erecting Stonehenge some 3,500 miles to the east, oak, hickory and chestnut forests in coastal Delaware were creating an environment rich in food resources, both animal and plant-based. For the first time, the smell of salt air may have wafted its way to the present-day corner of Mulberry Knoll and Cedar Grove, as the sea had nearly completed its advance over the continental shelf, lapping against the sandy perimeter of the Delmarva sand spit.

Around this time, as rivers coursed their way through the thick forests, emptying into large brackish marshes, humans began to settle near these watery resources, scooping up oysters and catching fish.

With this development came coastal Delaware’s first real estate boom. Circular structures measuring up to 20 feet in diameter, their post holes anchored in the soil, sprung up like mushrooms in natural clearings near the forest canopy. Fresh water was collected in pottery of brown and black. And some stone materials from as far away as today’s Ohio prove the exodus to Delaware’s beaches did not begin with the building of the boardwalk.

In a cabinet at the Nanticoke museum, in colors ranging from jet black to sparkly white, scores of delicate arrowheads lie, their points aligning in the same direction. They reflect a relatively recent technological breakthrough: A little over 1,000 years ago, the bulky stone spearheads that had dominated the hunting market for millennia were rapidly replaced with lighter, triangular arrowheads like these. Today’s military drone operators are direct descendants of these innovative hunters, who invented a way to kill safely, from a distance.

Peering from the forest’s edge, its tail twitching nervously, a sentient deer would have muttered, “They’re ruining everything.”

The Truck in the Cornfield sign, circa 1600:

“Wooded Lot: 1.6 Million Acres!”

The first Europeans to view coastal Delaware took one look at the forest that pressed up against its shores and thought one thing: “We can’t wait to cut that all down!” The fact that there were already people living there — hunting and fishing and trading furs — was more of an annoyance than a concern.

The grim history of Europeans — primarily English — evicting and sequestering the people who had lived here since before the pharaohs ruled Egypt is a sad litany played out from here to the Pacific. And the wild, in some ways savage, manner in which they transformed the land nearly defies comprehension.

You need look no further than the local Letters to the Editor to sense the distress — and sometimes rage — that can be inspired by the sight of local forests being mowed down in the name of new housing developments with names like Woody Glen and Nature’s Rest. But today’s bulldozers are mere amateurs compared to our saw-wielding ancestors. In fact, after a slow start, during which settlers cut down just enough trees to provide hand-split timber for their houses and small forts, the Europeans developed an appetite for wood that can only be described as voracious.

Sawmills, powered by creek water pouring over rustic dams, industrialized the process of devouring the coastal Delaware forests. Boards, oak barrel staves and cedar shingles bound for Europe sailed aboard ships built in Lewes and, later, Milton. Some of those vessels were, themselves, up to 100 tons. Next, as the iron industry flourished, forests were burned to create the charcoal necessary for production. The railroads gobbled up every native oak tree in sight to cut enough ties to lay tracks from Wilmington to Pocomoke.

“DuPont used a lot of lumber to make gunpowder,” adds longtime forester Tijade, referring to the explosive’s charcoal ingredient.

Of course, trees are astoundingly resilient organisms, and those leveled forests soon gave rise to second- and even third-generation iterations. Then, around the mid-20th century, large-scale farming exploded.

“From around World War II to roughly 1980 or ’90, farmland was prime,” says Tijade. “So a lot of clearing occurred for that.”

Delaware, which was once wooded from ocean to bay, is now one-third forest.

I ask Tijade if there is anywhere in the state that has anything approaching a primeval forest. He hesitates.

“Maybe in the cypress swamps,” he allows. “But even there, the bald cypress and Atlantic white cedar stands are largely gone, because the seasonal water fluctuations they need have been affected. Drive by any of those, or go out in a boat, and you’ll see a lot of them have died.”

“So, in answer to your question, no, I’m not aware of any.”

One forested area persisted through the ages: an 800-acre parcel owned by Issac C. Harmon, a member of the Nanticoke tribe.

“He was my grandfather,” says June Morningstar Robbins, curator of the Nanticoke Indian Museum. “The largest landowner in the area.”

Not until after Harmon’s death in 1900 were pieces of his land sold off. Much of it went to farmers. And that’s when the trees began to fall.

“People look at a farm field now and say, ‘Oh, that’s always been a farm field,’” says Morningstar, glancing across the museum floor to a diorama of an indigenous people’s creek-side community.

“But it probably hasn’t been a farm field all that long.”

The Truck in the Cornfield sign, circa 2124:

“Coming: New Oceanfront Lots!”

So, those are the countless moments leading up to the instant I turned left onto Mulberry Knoll Road. Now comes the future: a purchase of the land beneath the truck, followed by hearings, complaints and compromise. Before too long the truck will be towed off and bulldozers will arrive to flatten the soil, unearth some arrowheads, maybe reveal a forgotten grave or two.

One thing is for sure: Soon the cornfield will be an all-but-forgotten remnant, replaced by families in moving trucks, parents tucking their children into bed, retirees playing pickup pickleball games. In a few decades, there’ll be nobody left to drive by and sigh, “I remember when this was a cornfield in the middle of nowhere” — just as no one walks through Times Square and thinks, “I miss the sheep meadow that used to be here.”

But here’s my question: Then what?

After the two decades of explosive development coastal Delaware has just endured, it’s tempting to think new housing construction is the new permanent wave. We envision an eternal conga line of retirees, families and schoolchildren cha-cha-ing south on Route 1. But here’s an interesting tidbit: According to the Delaware Population Consortium, between 2025 and 2030 the number of households in Sussex County is expected to grow by about 7 percent. But jump ahead, and between 2045 and 2050 that growth is expected to be less than 2 percent.

The state’s numbers don’t extend to a point where the county will be seeing negative numbers, but it’s not hard to see where the trend is going.

That’s a concern of Jim Lee, who may be Delaware’s only professional futurist. He runs Strategic Foresight Investments in Wilmington — predicting trends in finance and society — and is a member of the Association of Professional Futurists.

While increased life expectancy will delay the inevitable, Lee says, declining birth trends will someday result in a housing glut — even at the beach. To understand the peril, you need look no further than Detroit, which has been demolishing entire unused neighborhoods due to population shifts.

“In the U.S.,” he says, “we really haven’t seen a lot of plans for deconstruction, have we? Our whole system is predicated on growth, and we don’t know what it looks like to undo growth.

“We’re a lot better at addition than subtraction.”

Our location near the beach complicates things, as well.

“Nature tends to engineer its own renewal,” he says. “Because you’re looking at a shifting boundary and rising sea levels, you’re looking at something that tends to be a bit more vulnerable to economic and environmental change.

“To that extent, you can never think of any development on a waterfront as being particularly permanent.”

It’s unlikely the Delaware beaches are about to return to the days of most businesses closing for the winter. The Tanger Outlets will not soon beat their Old Navy into plowshares. Not in the short term, anyway — and by short term I mean in the next century. But seriously, does anyone expect the Coastal Club HOA will still be meeting the first Wednesday of each month 500 years from now? Is our army of stick-built houses any match for the onslaught of time?

Whenever I get myself into a twist over those guys paving paradise and putting up another parking lot, I take a brief drive along the backroads that still wind through the farmland just a few miles from where I live. It doesn’t take long to come upon an old house, once someone’s beloved home, collapsing under the weight of sprawling vines, trees growing through its broken windows, animals coming and going through the open doors.

We really are just here for a minute or two. We make the best of it while we’re around and, yes, occasionally put up the good fight.

But I won’t pretend the truck in the cornfield knows the future. Only the land — and water — beneath it do.