For the men stationed at Fort Miles during World War II, recreation activities were abundant

By Michael Morgan

Photograph by Delaware Public Archive

From the April 2024 issue

“Just one year ago,” Delaware Coast News columnist Virginia Cullen wrote in May 1942, “the silent, saffron slopes of Cape Henlopen were known only to the wind and the tides; to a few straggling fishermen casting in the thundering surf. Where leisurely picnickers basked under the soporific sun. Where berry pickers for the sleepy little town of Lewes gathered wild plums and cranberries in the spring.” But since then, with World War II underway in Europe and the clouds of that conflict drifting across the Atlantic, construction crews had invaded the peaceful sands of Cape Henlopen to begin work on Fort Miles, which would become one of the most modern military installations on the East Coast. Eventually, massive concrete gun emplacements, bunkers and the ubiquitous spotting towers were built on the sands of the cape.

Sprinkled among these instruments of war, however, were tennis courts, a baseball diamond and other recreational facilities for the more than 2,000 men garrisoned at the fort.

The soldiers who arrived there in late 1941 were housed in tents while more permanent barracks and other buildings were being constructed. But, as the Smyrna Times reported, “the service men have had no gathering place when off duty at camp, except to roam the streets of Lewes and nearby Rehoboth.” In October of that year, the Lewes firehouse on Savannah Road was converted into a USO (United Service Organizations) facility that provided entertainment and social activities for active-duty troops. A month later, the newspaper noted that “the large hall, measuring 500 feet in length, will become a handsome clubroom with new maple furniture, floor lamps, draperies, and game tables. … Besides the regular weekly dance night there will be a ‘special feed’ night once a week when hostesses from various towns will provide special refreshments for the service men.”

According to a news clipping in the Lewes Historical Society archives, “On dance night they get the prettiest lassies of nearby towns as partners brought out under the chaperonage of Lewes and Rehoboth Beach matrons. The dance music is the best to be had — it should be because the orchestras are composed of many service men who once played with ‘name bands’ of the country.”

Two months after the USO opened, the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor thrust the United States into World War II, and the men of Fort Miles suddenly found themselves on the front lines. German submarines prowled Delaware waters. The U-boats began sinking freighters, tankers and American warships in the nearby shipping lanes. Many of the survivors of these attacks landed in Lewes.

While the soldiers at Fort Miles worried whether the next attack would come from the air or the sea, many of the wooden barracks were finished to replace the tents that soldiers had been living in for six months. Each battery, however, had its own “dayroom,” a recreation building for off hours when the soldiers could not leave the post to visit at the USO Club in Lewes. The government built the dayrooms, and various civic groups furnished them.

One of the most elaborate ones at Fort Miles was furnished and decorated by Woman’s Day magazine. Nineteen feet wide by 72 feet long, it featured a simple color scheme of three bright colors — red, green and yellow. Curtains were hung on the windows, and six new bluish-green rugs made of fiber matting were placed on the floor. The furniture was arranged in six living room groups with a unifying color in each. Some groups were covered with solid red, green or yellow fabric. Others were upholstered in material with green and white or red and white stripes. Scattered around the room were a radio, piano, pool table, table-tennis area, a telephone booth, bookshelves containing technical Army books and four stoves.

According to Woman’s Day, “We used the backs of all the tall pieces such as desks and bookcases, for bulletin boards, furnishing them with soft wallboard and molding, so that the boys could put up ‘pinup’ girls. We added big, generous ashtrays to each group.” When the dayroom was completed, the interior of the building provided a comfy setting alive with a rainbow of hues while the exterior of the sand-colored building blended into the gritty dunes. The dayrooms were also decorated with pictures created by soldiers during their off time. (See “The Fort’s In-House Artists,” page 57.)

In the evening, soldiers spent much of their free time in these spaces or in the barracks, writing letters to family and friends on USO-provided stationery. In 1943, Pvt. James Meisler wrote to his friend Ann Holland, “No letters to answer. … Worked like hell today, doing W.P.A. work you know shoveling sand and such.” Sometimes, Meisler was relieved of his normal duties, but that did not result in free time. “Saturday was one of the nicest days, and I had to spend it in the kitchen. Oh unhappy day. I always dread that place. … I bet I peeled ten thousand spuds. Plus washing enough dishes to feed a regiment on.”

Fort Miles had an extensive sports program to promote physical fitness and build morale. At the baseball diamond, soldiers competed against teams from the various batteries and played visiting teams from other military posts. At that time, Philadelphia had two major league franchises, the Phillies and the Athletics, and Pvt. Meisler, a dedicated sports fan, listened to broadcasts of their games. He also played on one of the fort’s baseball teams whenever he had the chance — which wasn’t as often as he wanted. Meisler complained, “Our ball team has been playing ball but it seems every time they play I’m on some detail. I’m hoping I’ll be able to play Wednesday when they buck up against Milton High School. I know I’ll be Beach Guard or M.P. Guard that day.”

Volleyball and touch football games were held on the field opposite the Post Exchange until hot weather, when they moved to the cooler beachfront. After A Battery won a volleyball tournament, the victors were awarded a banner they hung in their mess hall. The fort also staged a “camp Olympics” that featured such events as a 400-yard relay (in which rifles instead of batons were passed), a shot-put competition (using dummy hand grenades) and an obstacle course. Meisler was part of the A Battery teams, and he was reputed to be one of the fastest men on the post. He was a member of two winning relay teams and the sole winner of the obstacle course race.

During the winter, several of the batteries formed basketball teams. The headquarters team was the powerhouse of the Fort Miles tournament, and they rolled over the opposition from other batteries to a perfect 15-0 record one year. According to Wilmington’s Sunday Morning Star, “It was, however, discouraging that, because of the location of the camp, college teams were not within a practical distance to be scheduled.”

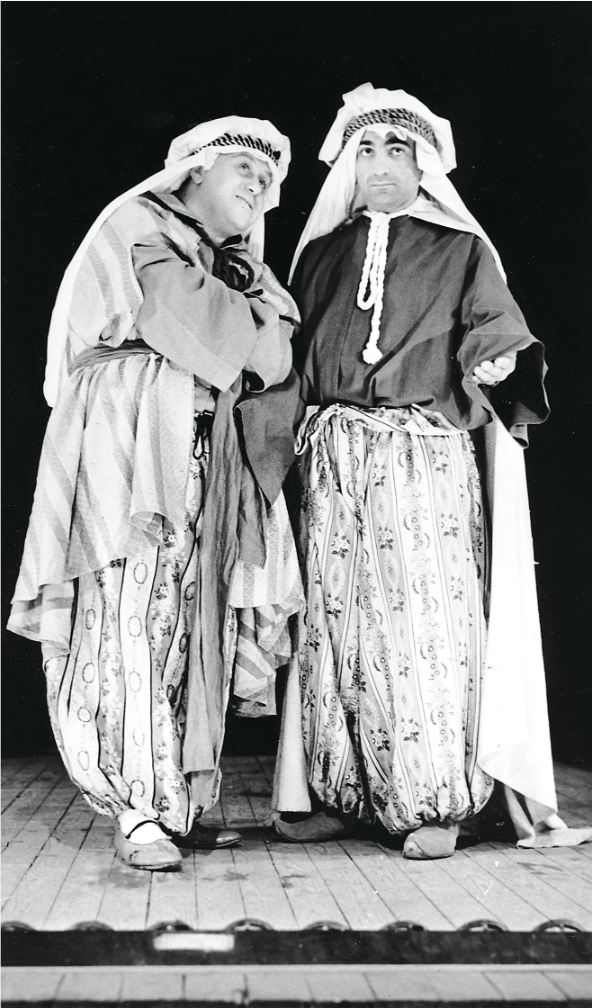

For soldiers who were not athletically inclined, the Fort Miles Players was formed to entertain the troops. The group’s first production, a revue titled “Here We Go,” was performed at several Army installations and at the Playhouse at Wilmington. “Dog Tags of 1943,” the second effort by the Fort Miles Players, was the brainchild of Cpl. David E. Fitzgibbons, a Broadway stage veteran. The new show had a cast of 12 soldiers, many of whom, like Fitzgibbons, were experienced performers before they joined the Army. The Star reported that the men “receive no special privileges for participating in the show and must perform their daily routine at the post, finding time for rehearsals.”

Preview performances of the new show were held in the Rehoboth Beach fire hall and in Georgetown. Audiences were composed of service personnel, who, the newspaper reported, “predict that it will be another smashing hit.” The female roles were played by male soldiers, and a highlight of the show was a trio singing “Why Did I Join the WAACS.” The three men appeared in uniforms of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, a comical look heightened by their Army-issued boots and less-than-flattering wigs. The productions of the Fort Miles Players provided a break in the military routine for both the performers and the servicemen in the audience.

With the Atlantic Ocean and Delaware Bay lapping at the edges of Fort Miles, the soldiers had an opportunity to enjoy the beach when they were off duty. The fish factories on the bay side, however, dissuaded many of them from those waters. In an oral history, one soldier remembered, “We aways complained about the awful smell, but we used to say that the people living in Lewes Beach would say that … [the smell of the factory meant] ‘Dividends.’ They welcomed the smell.” Along the ocean side, the officers took over the beachfront Belhaven Surf Club for their use. However, the ocean waters were sometimes so polluted with oil from ships sunk off the coast that Rehoboth residents kept a can of kerosene outside their homes in order to remove the oil that coated their skin.

The enlisted men who were lucky enough to receive passes would go to Rehoboth for the day to enjoy the boardwalk and movies. Not only was this a welcome escape from their military routines, but Rehoboth also had one of the few things the fort lacked — women. The resort also had a few drinking establishments. A member of the Fort Miles garrison recalled going to Edna’s Place in Rehoboth, which he labeled “a beer joint. … You go in there and get a sandwich and drink beer all night. You could get a pitcher of beer for about 25 or 50 cents.”

By 1943, with so many young men in the military and other vital industries, there was a labor shortage on Sussex County farms at harvest time. The New York Times reported on Aug. 1, 1943, that soldiers “went to battle at sunrise today to prevent loss of lower Delaware’s enormous lima bean crop. … Motorcades set forth from Fort Miles with coast artillerymen and from inland camps with infantry men.”

For the remainder of the war, the men at Fort Miles continued to enjoy their off-duty activities while attending to their military responsibilities. When peace came in 1945, the garrison was greatly reduced, and the “saffron slopes of Cape Henlopen” reopened to civilian fishermen, picnickers and people gathering wild plums and cranberries.