In ‘normal’ years, overseas guest workers flood beach resorts in summer, drawing comfort and support from an army of volunteers

By Chris Beakey | Photographs by Carolyn Watson

From the June 2020 issue

Editor’s note: As a result of the coronavirus pandemic, coastal Delaware business owners expect to employ far fewer exchange visitors in 2020. Reporting for this article took place during the summer of 2019, giving a view of the guest worker experience in a typical year.

It’s 5:25 on a Tuesday evening in June 2019, a happy yet nervous time for a dozen or so volunteers in the dining hall at Rehoboth’s Epworth United Methodist Church. After two hours of preparing sandwiches, salads and desserts, they can only hope their upcoming dinner will be a proper welcome for hundreds of young people from around the world who will be working in area beach communities in the coming months.

At 5:30, when she can no longer stand still, Rehoboth-area resident Fabiola Ciliberti steps into the lobby, where the glass doors reveal exactly what she’s hoping to see: a stream of young men and women bicycling toward the church. Moments later she resumes her position at the entrance to the dining hall and beside the three-piece band, a perfect spot for watching surprised smiles as the guests step into the room.

Initially, the atmosphere is reserved. The volunteers are retirees in their 60s and 70s who’ve lived in the U.S. for all (or most) of their lives. The guest workers are in their 20s and tend to speak quietly among themselves as they discuss their backgrounds and their summer plans. Half an hour into the dinner, in fact, the volunteers are still standing behind the buffet line after sharing little more than small talk with their long-awaited guests.

It all begins to change when Joan Rivera, who’s traveled from the Dominican Republic to work in housekeeping at the Atlantic Sands Hotel, approaches the three retirees in the band. He tells them he plays guitar from time to time and would be happy to step in for a song or two.

The local musicians are welcoming but not overly excited — until Rivera’s soul-stirring rendition of Luis Fonsi’s “Despacito” radiates throughout the room. It only gets better when the drummer eases into a salsa beat ... and better still when Ciliberti impulsively starts to move, her shoulders and hips in perfect rhythm as she eases onto the dance floor.

Within seconds she’s joined by more volunteers and guest workers who quickly lose their inhibitions to the joy of movement and the universal language of music. It’s a wonderful moment of camaraderie that extends into the rest of the evening, paving the way for cross-cultural experiences and international friendships that will flourish in the days and weeks to come.

Filling a need

Two months later, a trio of volunteers reflects on that opening night as a perfect example of how the International Student Outreach Program — which was founded by the Lewes-Rehoboth Association of Churches — welcomes and supports the nearly 1,000 international visitors who fill jobs in Lewes, Rehoboth and Dewey Beach during a typical summer season.

“These are bright, wonderful kids and what most of them want more than anything is to interact with American culture,” says Sue Sprague, who staffs the “help desk” at the free dinner Epworth offers every Tuesday during the summer. “We treat them the way we’d want our own sons and daughters to be treated if they were in a foreign country.”

“We learn so much from them too — some of the things they say just blow me away,” adds Deb Donovan, who offers advice and assistance during dinners provided on Thursday nights at The Lutheran Church of Our Savior near Rehoboth.

“I was never into adventuring when I was that age — sometimes I joke that I didn’t even cross

a big street until I was 40. I envy their spirit, the way they’re picking themselves up and experiencing the world.”

These sentiments are echoed by Maryanne Kauffman, who got to know Sprague and Donovan when the three retirees went to a conference in 2010 for employers using the J1 Visa Exchange Visitors program. All knew the basics of the program. The exchange visitors must be college students in their home countries. In addition to paying for their own travel, they have to pay fees to sponsoring organizations that help them find jobs and housing during their stay in the United States. A typical student can spend as much as $4,000 to work here for the summer — often in jobs that pay just above minimum wage.

“The program is well-established and well-run, but we learned about some tough challenges the students face — including how hard it is to find housing and get to and from work,” Kauffman says.

That realization inspired the International Student Outreach Program, called ISOP for short, to collaborate with the Delaware Department of Transportation to vastly increase the number of bikes available to the guest workers. Today — that is, when a global pandemic hasn’t altered life for vacationers and those who serve them — DELDOT provides free bikes, along with helmets and a mandatory safety course, to about 200 foreign visitors every year. Thanks to Kauffman’s husband, Bruce, and a group of talented mechanics, the guest workers also get free repairs all summer long.

ISOP also fosters cultural interactions by offering day trips to Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and Cape May, and helps the visitors save money by serving the free dinners offered at four local churches on different nights of the week. By season’s end, the churches typically will have provided close to 5,900 meals.

While ISOP tends to run efficiently, volunteers are proud of their capacity to solve problems that occasionally arise. In 2016, for example, 50 students from Turkey had nowhere to stay after being mistakenly told they could wait until they arrived in Rehoboth to find housing for the summer. With help from local real estate agents and hoteliers, Sprague, Donovan and Kauffman worked nonstop over a 24-hour period to find local residents and landlords who opened their homes or made rooms available.

They also recognized the possibility of disaster with the approach of Hurricane Sandy in 2012 when they learned there was no clear evacuation plan for the visiting students who were still working that fall.

“It took a lot longer than we liked, but we got meetings with people from the Delaware Emergency Management Agency, the Delaware State Police and others to make sure there were procedures for protecting the safety of these kids,” Donovan recalls.

“Yeah, we were in the secret bunker where they plan these things — got to see the special room,” Sprague adds. “Now there’s a plan to get ’em out of here if a big storm like that happens again.”

Cross-cultural mission

Over lunch at Obie’s by the Sea, in between his shifts at the Atlantic Sands and a second job as a dishwasher at Dos Locos, Joan Rivera expresses deep gratitude to all of the volunteers who are making his first summer in Rehoboth go so well.

“Everyone is so wonderful here — they say ‘thank you’ for everything,” he says. “Also — the work opportunities are so much better here. In my country we have salaries that don’t change no matter how many hours you work. It’s so much better to earn money for the hours and overtime too.”

Rivera, who’s studying in the Dominican Republic to be a civil engineer, speaks with pride of his work supporting the hotel’s cleaning crew and goes into great detail about the different products and procedures that make every room “just right” for the guests. Not once, during two hours of conversation, does he complain about the long hours or the hard work, and only laughs good-naturedly when describing how difficult it is to deal with “the little kids who bring all the sand in.”

A few miles away in downtown Lewes, fellow Dominican Republic native Rendey Marte-Mejia and Sergiu Repesco, from Moldova, also see America as a land of opportunity as they talk about their friend and employer, Matt DiSabatino, at Striper Bites restaurant. As Marte-Mejia puts it: “I came here for the first time in 2018 and was offered a job as a dishwasher — but after a month Matt came to me and said, ‘I don’t want you to do this forever.’ He worked me up to salads and even offered me more money. I feel connected to him because he’s such a good human being and because working here is like being with my family, but it’s also giving me the chance to learn everything about American culture. I learned some English in the Dominican Republic, but I know I’m getting better by being here and practicing all day.”

Repesco understands the challenges all too well. He spent his first summer here in 2010, initially working on a housecleaning crew. While he was happy to have the job, he wasn’t clocking enough hours to come out ahead financially. A second job in the stock room at Lingo’s Market in Rehoboth boosted his pay and forged an important new opportunity.

“At Lingo’s I knew I needed to work up more courage to learn how to speak English fluently,” he says. “Jessica Lingo was my manager — and such a nice person. She let me work at the register for a few hours a week and then longer when I became more comfortable talking to the customers.”

That proficiency enabled Repesco to move on to Touch of Italy in Lewes, and then to his job as a server at Striper Bites and a budding career as a photographer as well. Repesco, who now owns a home and lives in the area full time, emphasizes that none of it would have been possible without the broad network of friends he’s made along the way.

“People I meet are very curious to know where we’re from, how we got here and what kinds of problems we face,” he says. “It makes you feel so welcome. It was hard to decide if I should move here. But in my country, I could work as an engineer and barely earn enough to survive. Here I get to work with people like Matt and afford a nice house and a car and still send money to my family back home.”

DiSabatino smiles modestly when he learns how the two young men have described their experiences, and emphasizes the mutual benefits of bringing exchange visitors to his team.

“I’m glad I took the time to learn what the program was about when I was first starting my restaurants,” he says. “It’s very well organized. It creates experiences that are good for the visitors and for us as business people. And all of the [visitors] we’ve hired have been very dependable and successful.”

DiSabatino, who began his life in the hospitality industry as a busboy at the Rusty Rudder when he was 16, also sees restaurants as a perfect venue for learning about American culture alongside locals.

“Restaurants are the heart and soul of a community — they really help you understand what that community is all about,” he says. “Working at the Rudder as a teenager was a wonderful way for me to spend time with adults, and it’s magical when you see local kids making friends with these visiting students. They all realize it takes quite a few hands to reach a common goal at the end of the day.”

Finding their place

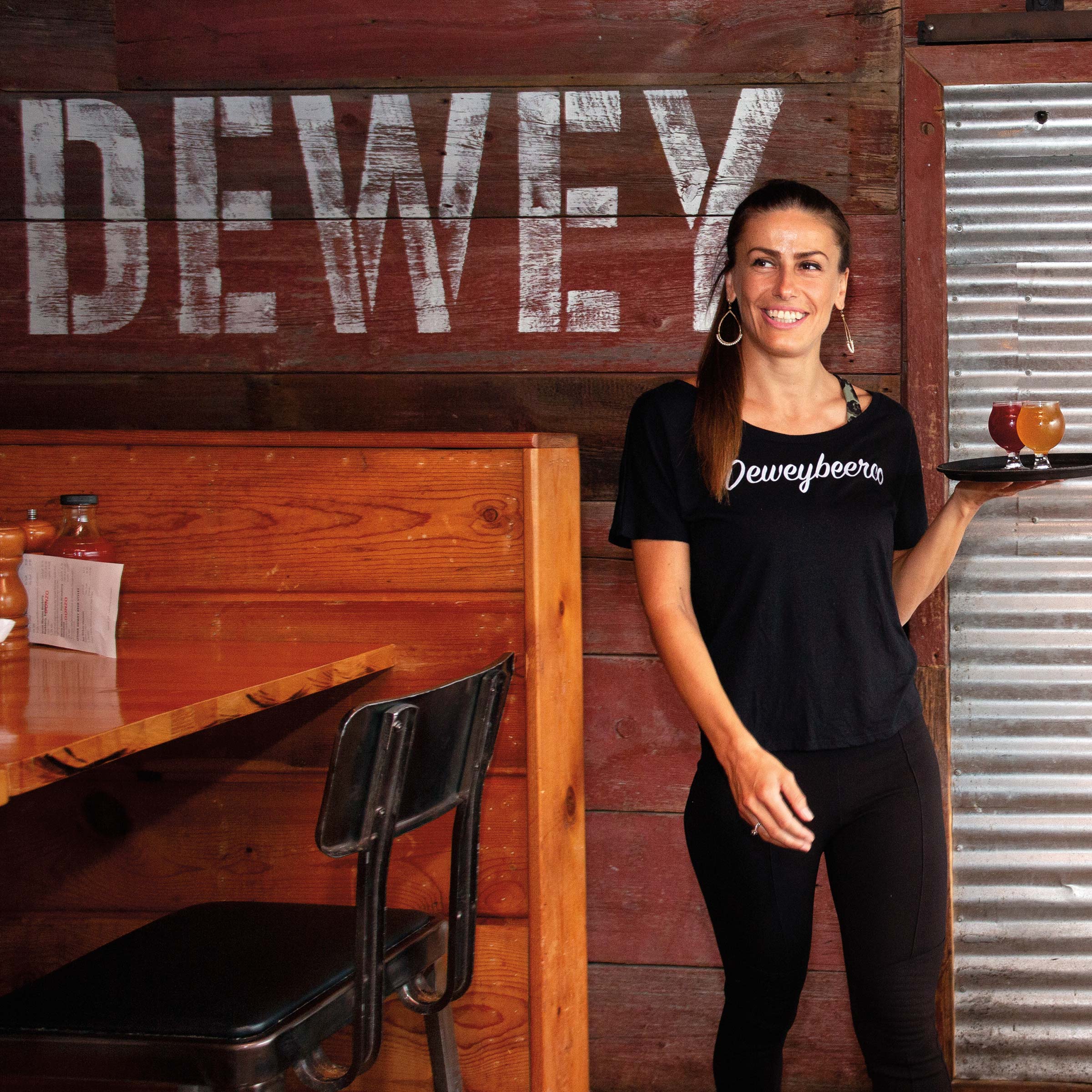

After a long day at the Dewey Beer Co., Lora Nacheva is equally enthusiastic about America’s economic opportunities. Yet she also shares cautionary tales based on years of past experience running her own in-country agency for exchange visitors traveling from her homeland of Bulgaria to work in the U.S.

“I was always part of the process,” she says. “I learned about the jobs here, told the employers about the students, set up the interviews and coordinated with the sponsoring organizations in the U.S. when the job offers were made. But I also stayed in close contact with all of my students while they were here. I often had to counsel them when they were lonely, or when they had trouble with their jobs or struggled with cultural issues.”

Then celebrating her 12th year of working with beach community restaurants, Nacheva credits her success as a former J1 program facilitator to her firsthand understanding of the culture her students bring with them as well as her affection for American life.

“I grew up in a small mountain town with narrow roads but loved American movies and TV shows — ‘Home Alone’ and ‘Friends’ were my favorites,” she recalls. “I always thought there must be so many opportunities in this country, and now I know I was right.”

During the “slow seasons” at the beach she has traveled to the Grand Canyon and several American cities (“Washington, D.C., is my favorite, especially with the blooming cherries,” she says with a smile). But she loves coming back to the Cape region.

“Every day’s a good day at work,” she says at the end of a long shift at the restaurant. “We play music in the kitchen where everybody’s dancing and making jokes and out in the dining room we’re always smiling and having fun with the customers. Nobody treats us differently than they’d treat an American. I think if you’re nice and fun, people are fun back.

“That’s why I’m in the U.S.,” she adds after reflecting on the possibility of becoming an American citizen someday. “I know I’ll never get anything easy. I’m lucky to have so many friends helping me, but I know I need to work hard for everything I want to achieve.”

That’s welcome news to Rehoboth-Dewey Chamber of Commerce Executive Director Carol Everhart, who was at the helm in 2006 when the organization mounted its early efforts to support the exchange visitors, and before ISOP stepped in.

“We’re so happy ISOP is here — they’ve done a wonderful job of organizing everything these students need,” she says. “I’m also happy to convey that our businesses recognize the guest workers fill a void — I don’t know how we’d fill these jobs without them.”

Taking friendship to heart

ISOP volunteer Chet Polusny, who learned Bulgarian prior to being stationed in the Balkan nation as a member of the Air Force during the 1960s, also believes exchange visitors are vital to a successful economy in the beach communities. He also sees a deeper context based on the friendships he’s established with many of these young people, and during his recent travels to Bulgaria, Romania, Macedonia and Albania.

“They’re always looking for ‘job number two’ so they can make the most of their time before going back to their home countries, which may be struggling to evolve into successfully functioning capitalistic societies,” he says. “It’s fun for me to see these kids learning about us. Everyone at ISOP wants to make sure they don’t get taken advantage of because they’re driven to work so hard, and [we] want to make sure they go home with good stories.”

Back in Rehoboth, at another well-attended exchange visitor dinner, Sprague, Donovan and Kauffman are thrilled to hear people saying good things about ISOP. Yet they all admit to lost sleep worrying about bicycle accidents and occasional conflicts with employers, and they frequently implore locals to open their homes to summer workers to deal with the area’s extreme housing shortage.

They also insist there’s no better way to spend their volunteer time.

“The students give me so much more than I probably give them, but I’m always there for a hug or whatever help they need,” Sprague says.

Donovan nods in agreement, and reiterates that cultural interactions will always be the driving force of the program.

“Our mission is to let them know they’re welcome and to be good ambassadors for the U.S. so they’ll go home and talk about an experience that reflects well on our country. But we also want them to know they’ve got our support. Every night at the dinners I walk around to the tables to let the kids know we’re here to help. They know whatever they tell me is confidential.”

“Same here,” Kauffman adds with a laugh. “In other words, we’re their mothers.”