Leaving Them With a Smile

- Details

- Written by Kris Legates

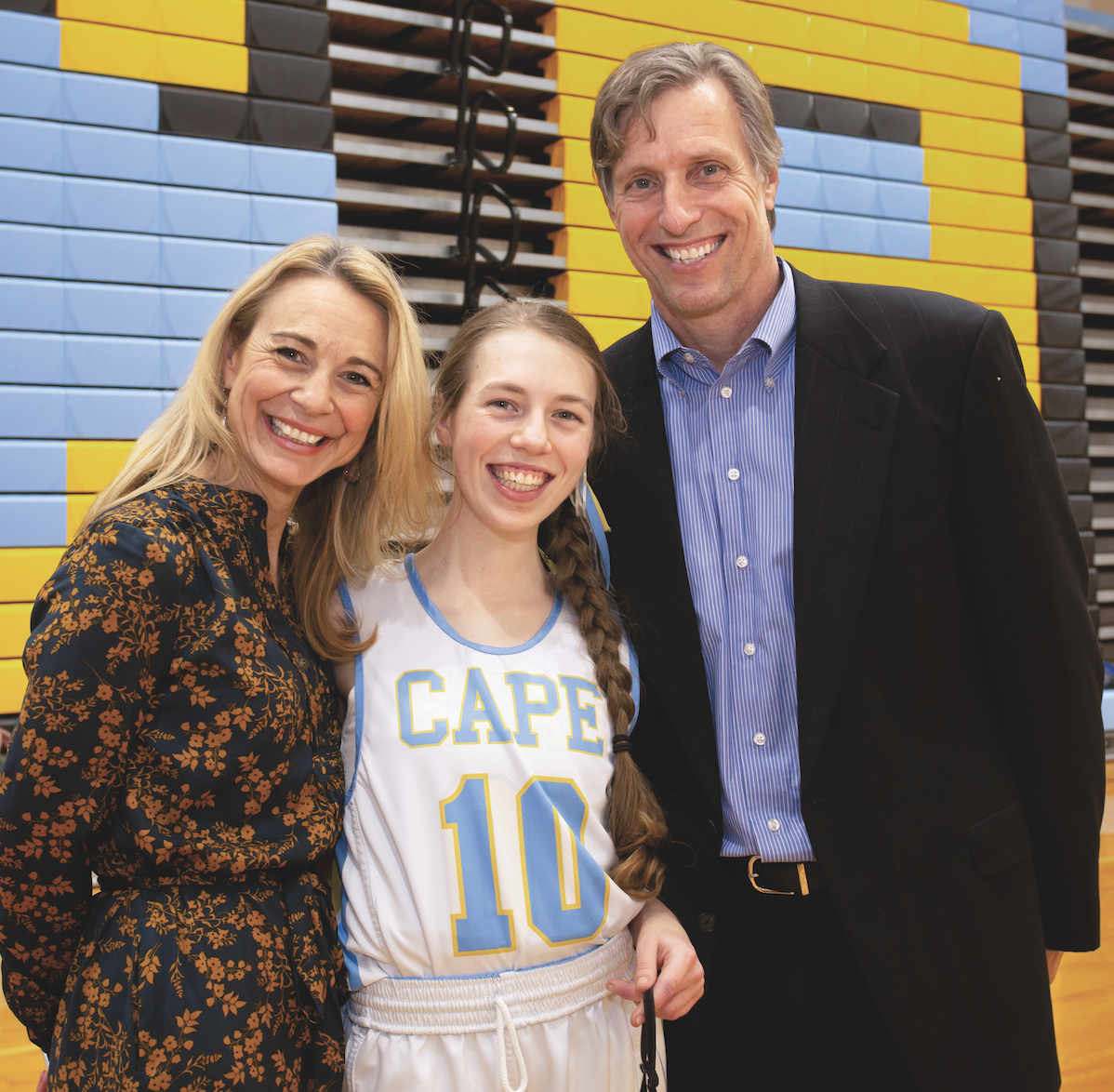

A rare genetic condition hasn’t dampened Elle Nauman’s gift for brightening others’ lives

By Susan Towers

Photograph by Carolyn Watson

From the May 2022 issue

Elle Nauman may know more students and teachers than anyone else at Cape Henlopen High School near Lewes. And those who’ve met the outgoing senior respond to the positive energy she radiates as well as her gentle nature — and her propensity to send text messages.

“All my friends text me after school,” Elle says, breaking into a broad smile that’s familiar to everyone who knows her. “She sends text messages to everyone, and they all message her back,” says her younger sister, Anna, a junior at Cape.

Health Care in Crisis

- Details

- Written by Kris Legates

COVID accentuated the pre-existing condition of staff shortages. In coastal Delaware, other factors heighten the need for a remedy.

By Pam George

Photograph by Neil Parry

From the May 2022 issue

Julie Short didn’t dither over career choices after high school. Like her grandmother, she attended Beebe Healthcare’s nursing school, now the Margaret H. Rollins School of Nursing. “I joke with my manager and say, ‘You know, I drank the Kool-Aid in the womb because I have grown up at Beebe,’” says the fifth-generation nurse, whose mother has worked at Beebe for more than 40 years.

“I have a loyalty to Beebe,” says Short, a rapid response and “code blue” nurse. (A code blue is called when a patient experiences unexpected cardiac or respiratory arrest that requires resuscitation.)

Birds of a Feather

- Details

- Written by Kris Legates

Migratory shorebirds flock to Delaware Bay beaches to feed on their way to northern breeding grounds

By Lynn R. Parks

Photograph by Deb Felmey

From the May 2022 issue

‘It’s not just people, yearning for surf and sun, who make annual treks to coastal Sussex. Migratory shorebirds — those stouthearted little creatures that travel thousands of miles every spring to reach their breeding grounds — include the beaches along Delaware Bay as a regular stop on their northward itineraries.

Up to 1 million shorebirds visit those beaches every spring, says Henrietta Bellman, a coastal avian biologist with the state’s Division of Fish & Wildlife. They represent as many as 30 species, including red knots, ruddy turnstones, semipalmated sandpipers, sanderlings and dunlins.

The birds typically arrive in late April and early May, Bellman says, with their populations peaking in mid-May. By the middle of June, they have left to continue their way north. Timing is everything in this journey: The shorebirds, exhausted and emaciated, arrive in Delaware at the same time that horseshoe crabs — like the birds, compelled by a centuries-old spring ritual — are crawling out of the bay to lay their eggs in the sand. The birds’ timely arrival along the Delaware Bay allows them “to forage during peak [horseshoe crab] spawning,” Bellman says.