An often-told family tale counters the Coast Guard’s 1930s report on a chicken house liquor stash

By Steve and Donna Bunting

From the April 2019 issue

In November 2017, Delaware Beach Life published an article about Prohibition headlined “Bootleggers on the Beach,” which mentioned the Coast Guard discovering “more than 200 sacks of illegal liquor in a chicken house in Bethany.”

According to that account, the booze was confiscated but the perps got away. As we read the story, we thought back to a family story, one we had heard many times, and smiled. What we knew happened that day in 1932 is somewhat different from the official record — and most certainly our family story was laced with far more colorful details. We figured it was time to correct the published account.

The Beach Life story cited as its source Eric Mills’ book “Chesapeake Rumrunners of the Roaring Twenties,” which in turn cites U.S. Coast Guard records, specifically “RG 26, Entry 283A, Box 1244.” If history tells us anything, it’s that (1) official reports often don’t tell the whole story and (2) official reports often portray the reporter in a favorable manner. Let’s move on with that in mind.

As the official story is told, an attempt was made to entice an Indian River Inlet Coast Guardsman, James S. Baker, to turn a blind eye to the offloading of illegal booze in the Cotton Patch Hills area between the inlet and Bethany Beach. Nothing is free, of course, and Baker was offered a sum of money, which he refused. Having failed to purchase his cooperation, the rumrunners fled farther south, toward Bethany Beach. The report would have you believe that the Indian River incident was linked to the chicken house in Bethany and that the Coast Guard investigated further, eventually discovering the stash there. (One hint that the account is suspect: This is where the creators of the report portray themselves in a favorable manner.)

As the Bunting family knows, the liquor seized in Bethany had nothing to do with the Indian River bribery attempt. Further, the Coast Guard had nothing to do with the initial discovery of booze in the chicken house. Rather, it was just pure luck that the local sheriff found it while going to shovel chicken manure, which was a purely personal chore of his.

What happened on Tuesday, Jan. 26, 1932, at 224 Maplewood St. in Bethany Beach is well established in our family history. The story has been told many times, no doubt embellished here and there to suit the moment, but the core facts have remained unchanged over the years. Alvin Bunting, father of Steve Bunting, one of the writers of this story, bore witness to these events. Alvin was about 6 years old at the time, but he remembered it in great detail, as most of it played out at the family home where he was born. We recorded his final telling of the story days before he succumbed to cancer in January 2005. As he said at the time, “I can remember it all, clear as a bell, just like it was yesterday.”

John and Florie Bunting, Alvin’s parents and Steve’s grandparents, had five sons and one daughter. John was a descendant of the first Bunting in the area, Jonathan, who was born in 1754 and resided in Selbyville where he ran a grain mill on a pond that is now mostly dried up or swampland. Large families in the early days were very much the norm. Buntings seemed to produce mostly boys (still true to this day). Hence, the local phone book listing for “Bunting” is a virtual family tree.

John and Florie lived on the corner of Maplewood Street and Coastal Highway in Bethany Beach. At the time, they owned the entire block, which was rather large. Behind the house, they maintained a large number of chicken houses of the type that were common at that time, i.e. the typical Sussex “broiler house.” The local poultry industry had been born just 10 years prior. The basic broiler house at that time was 16 feet by 16 feet and the height sloped down to about 4 feet in the back. You couldn’t stand up in that area and shoveling manure was back-breaking work. Alvin hated it, especially the strong ammonia fumes that made you cough and burned your eyes. Each house held about 500 chickens. There were scrub pines all around and many of the chicken houses were not visible from the main house, making them somewhat attractive for rumrunners if they were not in use.

One day the local sheriff, who was John Bunting’s good friend, stopped by and asked if he could have some chicken manure for fertilizer. John said, “Sure” and told the sheriff which chicken house was currently vacant and needed the manure shoveled out. Whenever you could get someone else to handle that thankless chore, it was a good day, or at least it should have been.

And so the sheriff, riding his horse-drawn wagon, went to the assigned chicken house. A short time later, he burst through John and Florie’s kitchen door, out of breath from running. He told John that the house was full of booze and that two men took off running when he arrived. The sheriff wanted to use John’s phone to call for help, which John most graciously allowed him to do. He called the local Coast Guard station in Bethany and that’s when, in Alvin’s words, “all hell broke loose.”

Soon, the siren at the station started going off to summon the guardsmen. Shortly after that the homestead was swarming with these responders, all of whom were armed with rifles and pistols. Young Alvin got his play rifle and was allowed to walk around with them as they went about their tasks. He remembered this quite vividly.

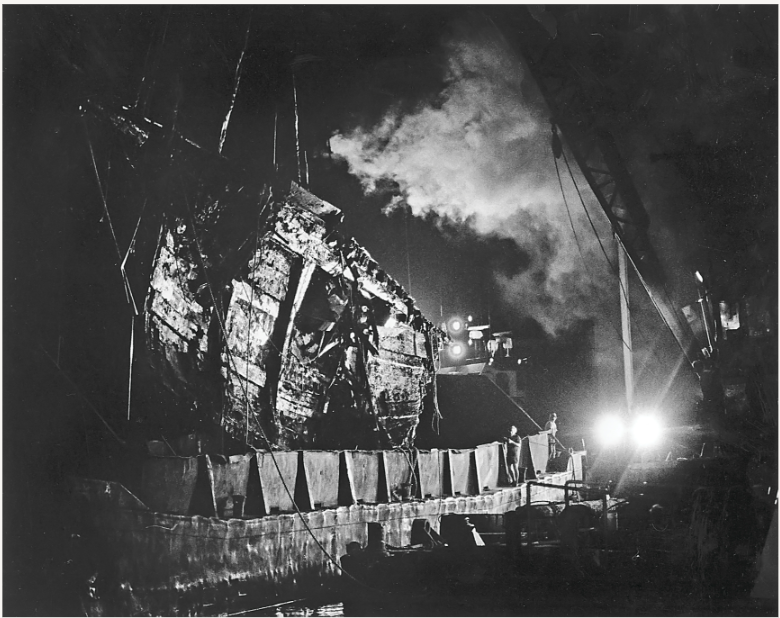

The official record states there were “219 sacks of assorted liquor stacked in a Bethany Beach chicken house.” A “sack” in those days was any container in which you could place your goods. It could describe a box (wooden or cardboard) or a bag (cloth or paper). Hence, the wooden crates in the official reports were called sacks. Alvin said there was both clear and amber-colored booze, all in wooden crates that were neatly stacked from floor to ceiling. A few of the boxes were open, but most were sealed.

Alvin and his father watched the Guardsmen as they transferred the contraband to horse-drawn wagons. Much of it was taken out of the boxes and placed in other containers. One could ponder why and therefore wonder how much was confiscated versus “put to good use” elsewhere. After all, it wasn’t needed as evidence, as the culprits got away!

Once done at the chicken house, the Coast Guard started to search the family house. At first John had no objection, as he had nothing to hide. However, the men were becoming destructive and when they wanted to pull up the floor boards to search there, John had had enough. He told the sheriff, “Do you think that if I was involved in this mess that I’d be stupid enough to send you to a chicken house full of illegal booze? And further, you know as well as I that Florie doesn’t allow a drop of liquor in this house!” He insisted that the law officer tell the Coast Guard to back off. It seems that the Coast Guard commander was convinced that John was not involved. With that, they all left — with the illegal booze, of course.

If he knew the identity of the fleeing culprits, John never said anything to the family. Bethany was a very small community, with no more than 100 residents in the winter. The pool of suspects was small. The pool was smaller yet for those familiar enough with the chicken houses to know which were not in use.

The story would seem to end there, but hardly! Almost two years later, Dec. 5, 1933, Prohibition was repealed and with it the quest to apprehend rumrunners. Attitudes changed regarding alcohol and, more importantly, tempers had a chance to cool off, especially John’s. And so it was at a family gathering that the truth came out. If anyone could be counted on to break the ice and tell what happened, it was “cousin Elias” Bunting, who happened to be one of the two culprits who had fled the chicken house that day. And thus we have the “rest of the story” straight from the horse’s mouth, cousin Elias!

Elias said, “Dad [Harry Bunting — John’s older brother] and I were in the chicken house getting some of the booze for some local folks when the sheriff pulled up. I took off running as hard as I could. No way was that sheriff going to catch me. No way.” He went on to say, “After a bit I started to get my wits about me and realized I left poor old Pop back there to fend for himself with the sheriff. I stopped to look behind me, but just as I did, poor old Pop went past me faster than a fox being chased by a hound, so I took off and could barely keep up with him.

“Eventually we stopped a long way off. We hid for a bit and then heard the sirens. We figured we’d better get out of the area pretty quick and we did.”

It seems the Coast Guard thought the booze was all going to the cities served by outsiders, but the local folks had a thirst for alcohol as well. Bethany, founded by a Protestant minister, had been dry since its founding and remained that way until 1982. Despite that, and despite Prohibition, people are people and they like to drink. Harry and Elias were just the pair to service that thirsty market. Alvin’s Uncle Harry had a couple of boats and could easily access Bethany and Ocean View via the many coves and creeks on the bay side. Harry and Elias had no need to pay the Coast Guard to look the other way. They could go offshore via the Indian River Inlet and return at will to those back bay waterways, completely unnoticed. After all, they were just local watermen, returning with their “daily catch”! The illegal booze didn’t all come ashore directly onto the ocean beaches by outsiders, as the Coast Guard seemed to think.

If John was ever angry at Harry and Elias, you never knew it. Alvin said, “Whenever Elias told this story, including the very first time, my dad laughed the whole time, especially the part about poor ole Pop running past Elias, his son.” Elias was a born storyteller and told this tale many times. He went on to be a charter boat captain, working out of Indian River and later in Florida. He was known for the big stogie he seemed to always have and also for the monkey “first mate” on his boat.

As the late Paul Harvey always said, now we know the rest of the story, the one not found in any official report, but the kind only found in family lore, passed down from generation to generation.