Letter to a Young Cop

- Details

- Written by Alissa Rosenstein

Even in a small resort town, there’s no vacation from misfortune and misbehavior

By Victor Letonoff Jr. | Photographs by Carolyn Watson

From the May 2020 issue

One sergeant reflects on the day-to-day challenges, sharing insights that might deepen the public’s understanding — and help new officers find their way in a demanding, sometimes confounding, career.

Dear Young Cop:

There’s so much I want to tell you and so very much I want for you: to serve without receiving injury; to end your career quietly after 20, 25 — even 40 — years with the knowledge that you have done your job well. I want you to be filled with pride every day that you put on your uniform, gun belt, ballistic vest (always wear your vest, young cop). Mostly, I want you to feel both awe and humility at what an honor it is to be a police officer.

But who am I to write this letter? I’m not a big city cop whose career was filled with drama: homicides, drug busts and high-speed chases. Instead, I’m a sergeant in a small Mid-Atlantic resort town with only three entrances into the city, one of them over an antiquated drawbridge. The ocean flanks one end of town along with an old-fashioned bandstand, where outdoor concerts are often held. Beyond that is a mile-long boardwalk, built in the early 20th century for patrons at the luxury hotels (so they wouldn’t carry sand into the elegant lobbies). The town, originally founded in 1873 as a Methodist church camp, is often described as quaint and upscale.

Getting Lost

- Details

- Written by Alissa Rosenstein

A day of deliberate wrong turns makes everything right

By Bill Newcott | Photograph by Carolyn Newcott

From the April 2020 issue

For the seasoned traveler, there’s nothing better than getting lost. If you never get lost, you never discover anything.

Alas, getting lost isn’t as easy as it sounds — particularly if you’re determined to get lost in the place where you live. There are street signs everywhere. Familiar landmarks keep popping up. And you have to resist the urgent temptation to switch on your GPS, “just to see.”

Despite the challenges, I was determined to get lost in coastal Delaware for a whole day; to explore unfamiliar back roads; to meet people who didn’t know anybody I knew. And so one recent morning I kissed my wife farewell, hopped into my car, and set out to get utterly disoriented.

Of course, even getting lost requires ground rules. I decided on a specific starting point and a final destination, to reduce the chances of just driving around in circles all day. Point A would be the Fenwick Island Lighthouse, hard up against the Delaware/ Maryland border. Point Z would be Cape Henlopen, site of the Fenwick light’s long-lost sister, the beacon that fell from its sand dune pulpit in 1926.

They Put the ‘Craft’ in Watercraft

- Details

- Written by Alissa Rosenstein

Local boatbuilders ride a 600-year tide of history

By Bill Newcott | Photographs by Carolyn Watson

From the Holiday 2019 issue

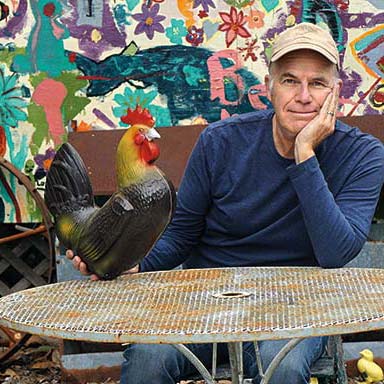

The 20-foot-long, cobalt-blue lake canoe occupies much of the length of David Greenhaugh’s driveway. Even to a guy who doesn’t know a dinghy from a deck boat, the workmanship is striking, the artisan’s attention to detail unmistakable.

Just above the bow, the canoe’s triangular deck plate — made of hard cherry wood — is stained like a fine piece of living room furniture. Inside the canoe, the gloss of white paint is smooth enough to see my reflection.

Between the white inside and blue exterior, embedded in the long, sweeping starboard gunwale at the top of the hull, a thin red strip of stained wood runs its entire length. This is the only evidence that the shell of this canoe is constructed entirely of redwood.