Shipwrecks abound along the coast of Delaware

By Pam George

Photograph by Marc Clery

From the May 2024 issue

It’s a typical sunny day, and beachgoers are taking a leisurely walk on the sand or, if the water is warm enough, splashing in the surf. It’s a peaceful, lighthearted scene. But unknown to many, the sparkling waves hide gloomy graves in the distance — or even beneath one’s feet. There are more than 2,400 wrecks in the waters around the Delmarva Peninsula, according to the National Geographic Society’s “Shipwrecks of Delmarva” map.

If the number surprises you, consider the presence of the two lighthouses on the breakwaters off Lewes as well as the Indian River Life-Saving Station (now a museum), all built in response to seagoing casualties in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Before modern weather forecasts, ships fell victim to sudden, devastating storms. Many were foiled by Delaware’s dangerous coast, which is littered with treacherous shoals, and German U-boats sank some during the world wars.

While the bulk of these wrecks occurred when Delaware’s waterways were commercial highways, hurricanes and northeasters continued to wreak havoc well into the 20th century. Here are some of the area’s most famous shipwrecks, many of which characterize the Delaware coast’s critical importance to transportation before planes, trains and automobiles.

The treasure-seekers’ dream: HMS DeBraak

Long before becoming a tourist destination, Lewes boasted a maritime economy based on shipbuilding, providing provisions and fishing. In 1798, HMS DeBraak, a British warship, stopped off the coast to get fresh water and let a local pilot board to take the vessel up the Delaware River. (That is still the case for inbound ships.)

Built by the Dutch, the DeBraak had been seized in an English port when war erupted in Europe. In 1798, it was escorting a merchant ship convoy when a foreign vessel appeared, and the DeBraak left to pursue it. (In those days, an enemy’s property was ripe for the taking.)

While separated from the convoy, the DeBraak captured a Spanish ship, perhaps near the Caribbean, and on May 25, 1798, the two vessels were anchored off Cape Henlopen when a sudden squall developed. The British had turned the DeBraak from a single-mast cutter into a two-masted brig, making it top-heavy, so the violent winds tipped the ship on its side like a toy boat. It took on water and quickly sank. Among the dead was Capt. James Drew, who was buried in the graveyard at St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in downtown Lewes.

After several failed attempts to raise the vessel, legends about it flourished. Many maintained that gold and precious stones were in the hold. After several salvagers failed to find the wreck, ghost stories blamed witches who supposedly guarded it.

The 1980 discovery off Florida of the Santa Margarita — with its millions of dollars in silver and gold — ignited new interest. In 1984, side-scan sonar located the DeBraak. But after a haphazard and unscientific search, the salvage company only found Royal Navy artifacts, not gold and emeralds. The company later sold the artifacts and a portion of the hull — which had been carelessly hoisted from the ocean floor — to the state.

Today, you can view some of those artifacts at the Zwaanendael Museum in Lewes and you can visit Capt. Drew’s grave. The state allows the public to see the preserved hull during scheduled tours at a facility in Cape Henlopen State Park. To arrange visits to view the DeBraak hull, call the Zwaanendael Museum at 302-645-1148.

Tragedy in the New World: Faithful Steward

The Faithful Steward’s story has all the makings of a disaster movie, complete with love lost, a fierce storm and human error. The ship carried 249 hopeful Irish immigrants, including multiple members from several large families. More than 100 were women and children. Because the new country they approached lacked a mint, the ship transported 400 barrels of British copper halfpennies and gold “rose crown” guineas.

The Faithful Steward left Ireland on July 9,1785, bound for Philadelphia. Dead seas and, perhaps, faulty navigation caused delays, but on Sept. 1, as the ship was finally nearing the mouth of the Delaware Bay, the captain decided to celebrate. He and his first mate got so drunk that they were carried to their beds, where they snored through the howling winds that accompanied an overnight storm.

Drifting in just 24 feet of water, the Faithful Steward struck a sandbar north of the Indian River Inlet, where punishing winds and waves tore the ship apart. The wreck was only between 100 and 150 feet from shore, but many passengers couldn’t swim. Moreover, women wore heavy, long skirts that dragged them underwater. In the end, only 68 people survived, including seven women and children.

In 1831, survivor James McEntire told the Meadville, Pa., Courier that he’d found his father and a sister on the beach, but his mother, another sister, and brothers were lost. The surviving passengers watched as thieves pulled bodies from the water to “plunder until they could plunder no more,” recalled McEntire, who suffered flashbacks for the rest of his life.

Occasionally, coins wash up on the stretch of sand between the inlet and the Indian River Life-Saving Station. It has happened so often that the area is called “Coin Beach.”

Mystery ship: the China Wreck

Divers don’t come to Delaware for the colorful fish and coral. They’re interested in the wrecks, and that was particularly true in 1970 when two National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration vessels stumbled on a wreck between Cape May and Cape Henlopen.

In the years after the discovery, those brave enough to endure swift currents and low visibility retrieved plates, saucers, cups, custard cups, tureens, ladles, casserole dishes and chamber pots. Because of all that tableware, they called the unknown ship the China Wreck.

Meanwhile, mystery-loving researchers used the salvaged china’s manufacturer insignias to date and identify the wreck. Most of it was English ironstone, created in the early 19th century to be an affordable porcelain substitute. Maker’s marks indicated that the bulk was made by Powell & Bishop (active 1867-1878), J.W. Pankhurst & Co. (1850-1882) and W.E. Corn (1864-1894).

Many maintain that the vessel is the Naples, Italy-based Principessa Margherita di Piemonte, which in 1891 sailed from Plymouth, England, bound for Philadelphia and carrying china. On March 12, the ship foundered on a shoal, and the Lewes Life-Saving Station rescued a Capt. Cassaregola and his 10-man crew.

However, the Principessa sank almost 20 years after some of the recovered china’s manufacturers ceased production. Would the stash have sat in storage that long before sailing? The John Sidney, en route to Philadelphia from Liverpool, was lost in a storm on Oct. 25, 1872, which is closer to the china’s production period.

The wreck’s identity remains unknown without a smoking gun — aka an item with a ship’s name — having been found.

Much of the cargo has been picked clean, but you can see some china at the DiscoverSea Shipwreck Museum in Fenwick Island.

Fire on the water: SS Lenape

The Delaware coast did not host many elegant ocean liners, but on Nov. 18, 1925, Lewes residents awoke to the sound of alarms: The liner SS Lenape was on fire off Lewes Beach. Curious onlookers watched flames shoot up to 100 feet into the air.

The ship was en route from New York to Jacksonville, Fla., with 350 passengers and 90 crew members. On Nov. 17, an engineer noticed smoke curling through a bulkhead vent in the cargo area. Saltwater pumps and fire hoses failed to extinguish the flames.

Near midnight, the crew roused sleepy passengers, including Julia Davies Arnold, whose story is detailed in Bob Kotowski’s book “Ablaze in Lewes Harbor: The Last Cruise of the SS Lenape.” Arnold put lifejackets on her three pajama-clad children and joined the other nervous passengers in the music room.

Delaware pilot boats answered distress calls and began rescue operations, but as the fire consumed the ship, some people grew impatient and jumped into the water. One man leaped while holding onto a rope, but he collided against the boat’s side and was the only fatality. Most of the injuries sustained by others on board involved broken ankles, exposure and smoke inhalation.

Town residents rallied to provide food and clothing to survivors, who later took trains to New York or Florida. There was talk of purchasing the charred ship for use as a break-water to protect the Cape Henlopen Lighthouse. Instead, the liner was sold for scrap, and the imperiled lighthouse tumbled from its eroding dune on April 13, 1926.

Unintentional Landings: Merrimac, Severn, Thomas Tracy and Black Spoonbill

Rehoboth Beach, founded in 1873, is not as old as Lewes, but it still sports some photo-worthy wrecks, including four that illustrate the force of Mother Nature.

For instance, on April 8, 1918, the tug Eastern left New York towing the barges Severn and Merrimac. When the tug encountered a fierce storm, it sought shelter at the Delaware Breakwater but strayed south. As the weather worsened, the tug cut free the barges, which drifted toward shore.

The 640-ton Merrimac slammed to a stop in front of St. Agnes by the Sea, a home maintained by Franciscan nuns at the end of Brooklyn Avenue. The Severn pulled up a short distance away. The two beached vessels became tourist attractions until officials wanted them gone in time for the summer season. A tug successfully refloated the Severn, but the Merrimac was so embedded that salvagers stripped all but the hull, which eventually settled into the sand.

On Oct. 6, 1957, Rehoboth got a brush with celebrity when a northeaster pushed singer/actor Burl Ives’ 62-foot yacht, Black Spoonbill, aground near the Indian River Inlet. When the accident occurred, the crew had been sailing the boat from New York to Palm Beach, Fla., and the force of the landing hurled them from the yacht onto the beach.

Legend has it that Ives — then famous for the movie “East of Eden” — refused rescuers’ help and swam to shore. While recovering at a bar, he reportedly raised a glass of whiskey and announced: “Gentlemen, when you’re struggling and when you’ve got pain, that’s when you know you are alive.”

However, the future voice of Sam the Snowman in “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” was in fact not on the $100,000 yacht. Reports circulated, however, that Ives visited to inspect the damage and then dined at the Dinner Bell Inn.

One of Delaware’s most memorable shipwrecks is the Thomas Tracy, a 250-foot freighter traveling south from New England when it encountered the Great Hurricane of 1944, which caused 390 deaths and more than $1 billion (in today’s dollars) in damages. In coastal Delaware, winds were clocked at 90 mph, blowing the roofs off houses.

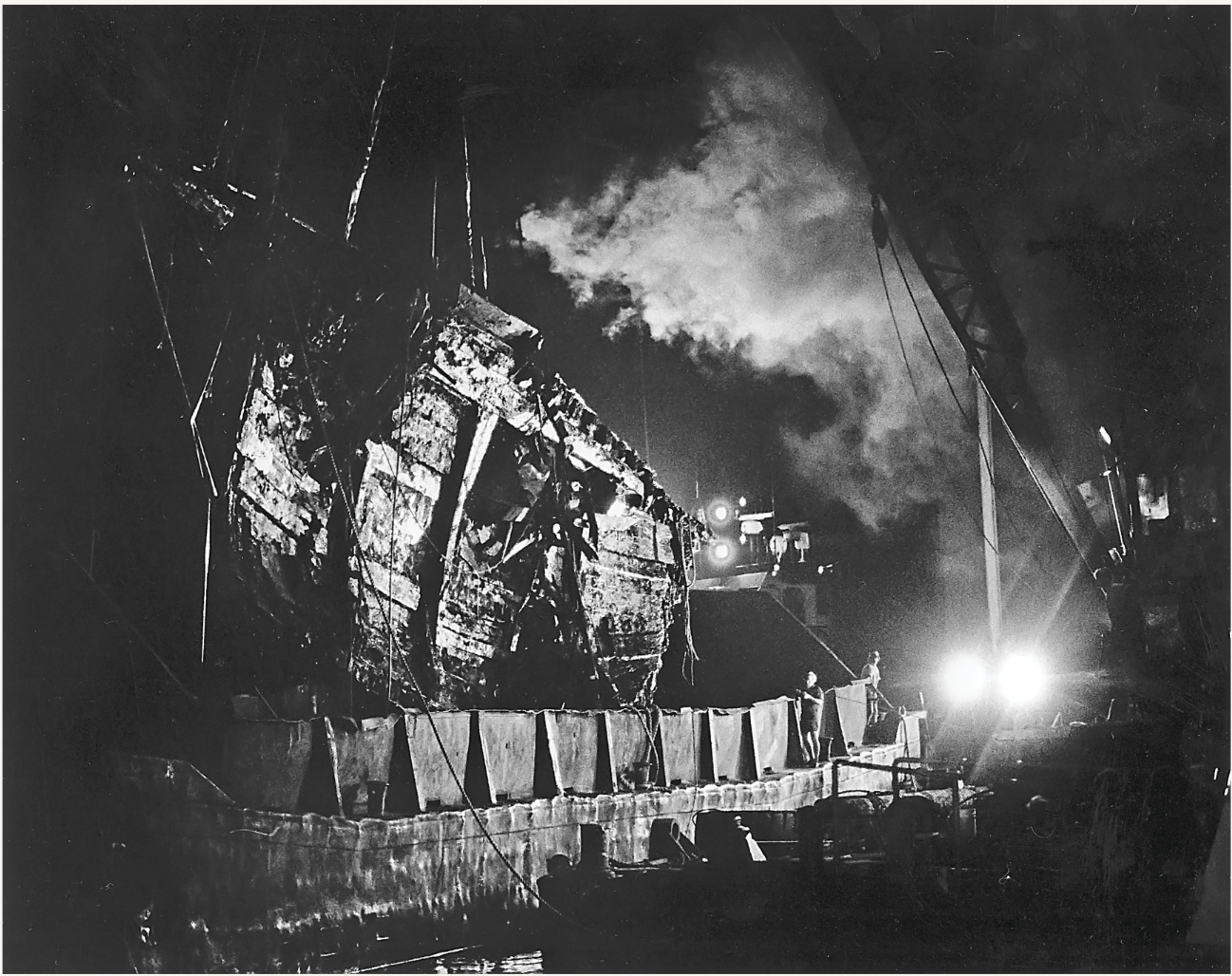

Built in 1916, the Thomas Tracy had survived German U-boats only to fall victim to the hurricane, which forced the behemoth onto the beach atop the Merrimac’s remains. To rescue the crew, the Coast Guard used a breeches buoy — a device with a rope line and a seat with cutouts for legs. The line was shot from the shore to the ship by a small short-barreled cannon called a Lyle gun. One by one, the crew slipped into the breeches and traveled via the zipline-like apparatus to safety. One carried a dog.

The ship groaned and swayed during the nail-biting rescue until it cracked in two. Once again, salvagers later cut the Thomas Tracy to the hull, just as they had the Merrimac.

Scrap removal, beach replenishment, tides and time have covered the remains. One day, however, new storms might reveal the unfortunate ships’ tombs.